Making an Art Bot, a Walkthrough

•

I had a great idea, to make a bot that could recreate abstract art in the style of several artists to make a fake art gallery. This is generally too big a scope for a regular Twitter bot project so I started with one that’s comparatively easy to replicate in code: Mondrian and his Neoplasticism style. The most famous Neoplastic works were perfectly vertical and horizontal black lines forming a grid on a white canvas, with some of the interior rectangles made by the grid filled with primary-ish color fields. This should be fairly easy to randomize and draw on an HTML canvas; this article is detailing the process by which the bot code was created and made ready for deployment to eventually power @neoplastibot.

Prelim 0: Drawing on a canvas:

I followed my “Steal everything that isn’t nailed down” rule by appropriating a bit of boilerplate code from Paul O’Leary McCann’s (@polm23) code for @dupdupdraw. I just needed to have something that would allow me to easily draw to the canvas, and I had worked on some enhancements for @dupdupdraw previously, so it was an easy decision.

Out of this we have a variable context from https://github.com/polm/dupdupdraw/blob/709240f/forthcanvas.js#L272 that represents a 2d canvas context, and a function writePng() from https://github.com/polm/dupdupdraw/blob/709240f/forthcanvas.js#L11 that takes a canvas and a file name, and outputs a PNG file to that file name. writePng is called at the end after the canvas is set

Prelim 1: Drawing random lines.

The first thing I wanted to do was put black lines in a grid at irregular intervals on a white background. The easiest way to start is to first draw a bunch of full-height vertical lines, then subdivide the space between each vertical line plus the left and right edges with horizontal lines.

First we’ll define a quick array sum function using Array.prototype.reduce:

function asum(arr) {

return arr.reduce(function(a, b) {

return a + b;

}, 0)

}

Then we’ll use that to generate random lines until the widths between those lines exceeds 512 pixels total

var xparts = [];

while(asum(xparts) < 512) {

xparts.push(Math.floor(Math.random() * 512));

}

Note that I’m going for conciseness here. It’s a Schlemiel’s algorithm (one where excess traversing happens), but it’s hardly a large enough data size to justify writing less terse code.

Now we’ll take our white canvas and draw black lines on it, marked by each line.

context.fillStyle = "rgb(0,0,0)";

xparts.reduce(function(offset, xp, i) {

context.fillRect(offset + xp, 0, 7, 512);

});

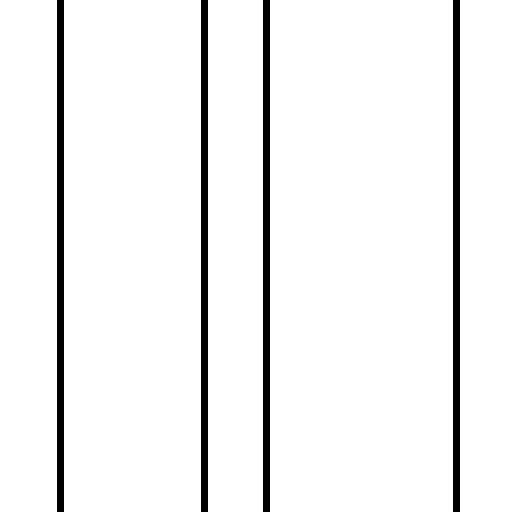

and the result of running it once.

I’m calling it a “line” here, but it’s really a 7x512px black rectangle.

One additional thing is to constrain the randomness a bit better. In essence, I’d like to make the boxes closer to a particular value but still allow randomness, with these steps:

- Enforce a minimum, by making the boxes at least 50px (about 1/10 the width or height of the canvas)

- Prefer smaller boxes in order to show more in the canvas.

I do this by changing my randomizer from the above snippets to look more like this:

xparts.push(Math.floor(Math.pow(Math.random() * 14, 2)) + 50);

Random mutliplied by 14, then squared, then floored, gives us values from 0 to 195; adding 50 gives values from 50 to 245. This guarantees at least two lines in each direction, and squaring the random value changes the distribution toward the lower values.

So the vertical lines are now set, but we need horizontal lines to break up the columns now. That’s pretty easy using the same pattern of randomness that we established for vertical lines, with the addition of mapping over the existing vertical lines (the “xparts”):

var yparts = xparts.map(function() {

var yp = [];

while(asum(yp) < 512) {

yp.push(Math.floor(Math.pow(Math.random() * 14, 2)) + 50);

}

return yp;

});

Drawing between the vertical lines isn’t too bad either; we just draw between zero or the sum of all previous offsets, to the current offset.

context.fillStyle = "rgb(0,0,0)";

xparts.reduce(function(offset, xp, i) {

yparts[i].reduce(function(yoffset, yp, i) {

context.fillRect(offset, yoffset + yp, xp, 7);

return yoffset + yp;

}, 0);

});

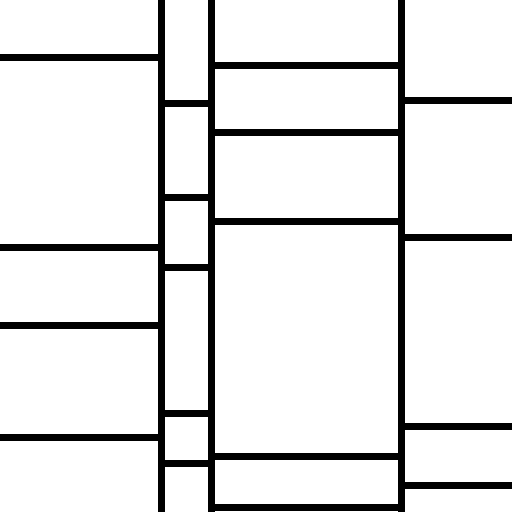

Now the script will give us a grid of black lines like this:

The edges aren’t filled with lines, but this reflects what actual Mondrian pieces tend to look like, so this is fine.

Prelim 2: filling squares

With the lines drawn, we can now get to work at randomly filling some of the delineated squares with primary-ish colors (red, yellow, and blue). We need to have an idea of how many squares we can fill in, so we’ll count all of the yparts for each xpart, then choose a random sampling of the total.

var fills = [];

var count = Math.floor(Math.random() * yparts.reduce(function(a, yp) { return a + yp.length; }, 0) / 2) + 1;

Now we’ll chose that many random blocks (a tuple of xpart and attendant ypart) to fill with a randomly chosen primary color.

var fillcolors = ["rgb(255, 255, 0)", "rgb(255, 0, 0)", "rgb(0, 0, 255)"];

var xp, yp, fill;

while(count--) {

xp = Math.floor(Math.random() * xparts.length);

yp = Math.floor(Math.random() * yparts[xp].length);

fill = fillcolors[Math.floor(Math.random() * fillcolors.length)];

console.log(JSON.stringify([xp, yp, fill]));

fills.push([xp, yp, fill]);

}

And fill them in on the canvas with simple block drawing. We have to use asum on the xparts and yparts to figure out the cumulative (x, y) offset where we start drawing. If we decided to start drawing at offset 0 in either dimension, we don’t add 7 to account for the width of the black line that we would account for in other offsets.

fills.forEach(function(fill) {

var xoff, yoff, w, h;

context.fillStyle = fill[2];

xoff = fill[0] && asum(xparts.slice(0, fill[0])) + 7;

yoff = fill[1] && asum(yparts[fill[0]].slice(0, fill[1])) + 7;

w = xparts[fill[0]] - (xoff ? 7 : 0);

h = yparts[fill[0]][fill[1]] - (yoff ? 7 : 0);

console.log("filling", xoff, yoff, w, h);

context.fillRect(xoff, yoff, w, h);

});

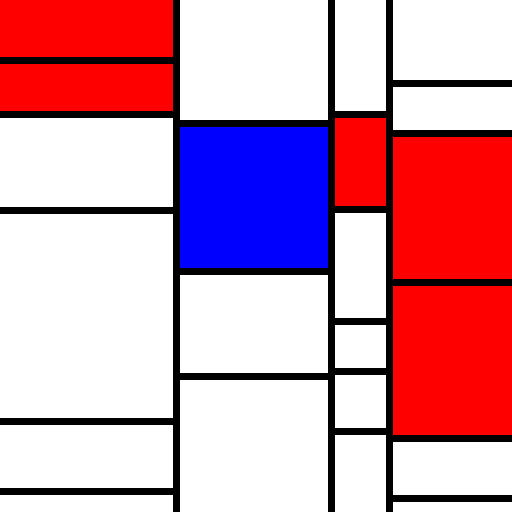

And here’s a sample that we’d get out of it:

This is great, but it’s got one major limitation, that the vertical lines always have to be drawn in the full. To move on from this to something more like a real Mondrian (with both horizontal and vertical grid lines being broken up at different offsets) we’ll have to change how we build the random grid. This will be covered in the next post.